ಜಗದನು ಕೇಳಿದ ಪ್ರತ್ಯುತ್ತರ

- kiran kulkarni

- Jul 8, 2025

- 5 min read

For english > Scroll down

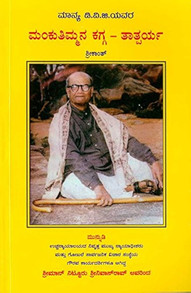

ಕಳೆದ ತಿಂಗಳು ನನ್ನಲ್ಲಿ ಏನೋ ವಿಚಿತ್ರವಾದ—but ಶುಭದ—ಪ್ರಕ್ರಿಯೆ ಶುರುವಾಯಿತು. ಎಲ್ಲವೂ ಎಷ್ಟು ಸುಲಭವಾಗಿ ನಡೆದಿದೆ ಎಂಬುದನ್ನು ಹಿಂದೆ ನೋಡಿದಾಗ ಮಾತ್ರ ಅರಿವಾಯಿತು. ನನ್ನ ಕೈಗೆ ಆಟ್ಲಾಸ್ ಶ್ರಗ್ಡ್ ಪುಸ್ತಕದ ಹಳೆಯ ಪ್ರತಿಯೊಂದು ಬಂತು—ಹಳೆಯದು ಆದರೆ ಅದರೊಳಗಿನ ಶಬ್ದಗಳು ಬಿರುಗಾಳಿಯಂತೆ ನನಗೆ ತಾಗಿದವು. ಜೊತೆಗೆ ನಾನು ಮತ್ತೆ ತೆಗೆದುಕೊಂಡೆ ಮಂಕುತಿಮ್ಮನ ಕಗ್ಗ—ಪುಸ್ತಕ ಅಷ್ಟೊಂದು ಸುಮ್ಮನೆ ಕೋಣೆಯಲ್ಲಿ ಇದ್ದಿದ್ದರೂ, ನಾನು ಅದನ್ನು ಸಂಪೂರ್ಣವಾಗಿ ಕೇಳಿರಲಿಲ್ಲ. ಇದರ ಮಧ್ಯೆ ನಾನು ಓದಿದ್ದೆ ಎಸ್.ಎಲ್. ಭೈರಪ್ಪನವರ ಆವರಣ—ಇದು ಕಥೆ ಹೇಳುವುದಕ್ಕಿಂತಲೂ ಹೆಚ್ಚು, ನಮ್ಮ ಒಳಗಿನ ನೆನಪುಗಳ ಗುಂಡಿಯಲ್ಲಿ ನುಗ್ಗುವ ಪ್ರಯತ್ನ. ಇವೆಲ್ಲವೂ ಸಾಗುತ್ತಿರುವಾಗ, ನನ್ನ ಹಿಂದೆ ಕೇಳಿಸುತಿದ್ದದ್ದು ನಿಖಿಲ್ ಬ್ಯಾನರ್ಜಿ ಅವರ ಸಿತಾರ್—ದಿನಗಳ ಬೆಳಕಿನಲ್ಲಿ, ರಾತ್ರಿ ಗಾಢವಾದ ಮೌನದಲ್ಲಿ ನುಗ್ಗುತ್ತಿದ್ದ ರಾಗ.

ಮೊದಲಿಗೆ ಈವುಗಳು ಕೇವಲ ಓದು ಮತ್ತು ಕೇಳುವಿಕೆಯಾಗಿತ್ತು. ಆದರೆ ಒಂದಿಷ್ಟು ದಿನಗಳಲ್ಲಿ ಅದು ಬದಲಾಗಿತ್ತು—ಇವುಗಳು ಕಲೆಯ ಕುರಿತು, ಬದುಕಿನ ಕುರಿತು ತಾವು ಏನೆಲ್ಲ ಹೇಳಬಹುದು ಎಂಬುದನ್ನು ತೋರಿಸುತ್ತಿದ್ದವು. ನಾವು ಯಾಕೆ ಕಲೆಯತ್ತ ತಿರುಗುತ್ತೇವೆ? ಕಲೆಯ ಮೂಲಕ ನಾವು ಏನು ವ್ಯಕ್ತಪಡಿಸುತ್ತೇವೆ? ಕಲೆಯು ನಿಜವಾಗಿಯೂ ಏನು?

ಅಯ್ನ್ ರ್ಯಾಂಡ್ ಮೊದಲಿಗೆ ತನ್ನ ಅಭಿಪ್ರಾಯವನ್ನು ಬಹಳ ಸ್ಪಷ್ಟವಾಗಿ ಹೇಳುತ್ತಾಳೆ. ಅವಳಿಗೆ ಕಲೆಯೆಂದರೆ ಕಲಾವಿದನ “ಮೌಲ್ಯ ದೃಷ್ಟಿಯ ಆಧಾರದ ಮೇಲೆ ಆವೃತ್ತ realities” – ನವೀನವಾಗಿ ರಚಿಸಿದ ನಿಜಾಂಶ. ಅವಳಿಗೆ ಕಲೆಯು ಕೇವಲ ಸೌಂದರ್ಯವಿಲ್ಲ, ಅದು ಆತ್ಮದ ನಿರ್ಮಾಣ. ಲೇಖಕರು ನೀತಿಶಾಸ್ತ್ರದ ಬುದ್ಧಿಜೀವಿಗಳು, ಚಿತ್ರಕಾರರು ತತ್ವಶಾಸ್ತ್ರವನ್ನು ಬಣ್ಣದಲ್ಲಿ ಬಿಡಿಸುವವರು. ಅವಳ ಪಾತ್ರಗಳು ಆತ್ಮವಿಶ್ವಾಸದಿಂದ, ದೃಢನಿಶ್ಚಯದಿಂದ ತುಂಬಿರುತ್ತವೆ. ಸಂಶಯಕ್ಕೂ, ಆತ್ಮವಿಮರ್ಶೆಗೂ ಅವಕಾಶವಿಲ್ಲ.

ಆದರೆ ನಾನು ಈ ನಿರ್ಧಾರಮಯ ಗಂಭೀರತೆಯಿಂದ ಮಂಕುತಿಮ್ಮನ ಕಗ್ಗದ ಮೌನತೆಯಲ್ಲಿಗೆ ಹೆಜ್ಜೆ ಇಟ್ಟಾಗ, ಎಲ್ಲವೂ ಮತ್ತೊಂದು ಜಗತ್ತಾಗಿ ಕಾಣಿಸಿತು. ಡಿವಿ ಗುಂಡಪ್ಪ, ಕನ್ನಡದಲ್ಲಿ ಎರಡೋ ಮೂರು ಸಾಲುಗಳಲ್ಲಿ, ಕಲೆಯ ಬಗ್ಗೆ ಮತ್ತೊಂದು ರೀತಿಯ ಮಾತು ಹೇಳುತ್ತಾರೆ. ಅವರು ಹೇಳುತ್ತಾರೆ: ನೀನು ಎಣ್ಣೆಯ ಹನಿ ಎಂತೆ ನೀರಿನ ಮೇಲೆ ಬೆರೆವದಂತೆ ಇರಿ – ಜಗತ್ತಿನಲ್ಲಿ ಇರು, ಆದರೆ ತಾಕದೆ ಇರು. ಅಯ್ನ್ ರ್ಯಾಂಡ್ ಒಂದು ಶಿಲ್ಪವನ್ನು ನಿರ್ಮಿಸುತ್ತಾಳೆ; ಡಿವಿಜಿ ನದಿಯಂತೆ ಹರಿಯುತ್ತಾನೆ. ಅವನು ಒಂದು ಚುಟುಕುಗಳಲ್ಲಿ ದೊಡ್ಡ ತತ್ತ್ವವನ್ನು ಹೇಳುತ್ತಾನೆ—ಹಗುರವಾಗಿ, ತೀಕ್ಷ್ಣವಾಗಿ, ಸಂತದಂತೆ.

ಆಮೇಲೆ ಭೈರಪ್ಪ ಬರುವರು—ಬೇರೆ ರೀತಿಯ ಗಂಭೀರತೆಯಿಂದ. ಆವರಣ ಒಂದು ಕಾದಂಬರಿ ಅಲ್ಲ, ಅದು ಒಂದು ತಾತ್ವಿಕ ಶೋಧನೆ. ಅಯ್ನ್ ರ್ಯಾಂಡ್ ತೋರಿಸಲು ಇಚ್ಛಿಸುವ ನೈತಿಕ ನಿಷ್ಠೆ ಇಲ್ಲಿಯೂ ಇದೆ. ಆದರೆ ಭೈರಪ್ಪರ ಪಾತ್ರಗಳು ತಮ್ಮ ಬುದ್ದಿಮತ್ತೆ ಮಾತ್ರವಲ್ಲ, ತಮ್ಮ ಸಮಾಜ, ತಾತ್ವಿಕ ಪಾಠಗಳು, ಧರ್ಮ, ಇತಿಹಾಸವನ್ನು ಕೂಡ ಹೊತ್ತಿರುವವರು. ಅಯ್ನ್ ರ್ಯಾಂಡ್ ವ್ಯಕ್ತಿಯ ಪ್ರಾಮುಖ್ಯತೆಯನ್ನು ಸಾರುತ್ತಾಳೆ. ಭೈರಪ್ಪ, ವ್ಯಕ್ತಿಯ ಒಳಗೆ ಇರುವ ನಾಡಿನ, ಧರ್ಮದ, ಹೀನ್ಮೆಮೆ ಮರೆಯಲಾದ ಸತ್ಯದ ತೂಕವನ್ನು ತೋರಿಸುತ್ತಾರೆ. ಅವರ ಕಥೆಗಳು ಉತ್ತರಗಳನ್ನು ಕೊಡೋಲ್ಲ, ಆದರೆ ನಿಜವಾದ ಪ್ರಶ್ನೆಗಳನ್ನು ಕೇಳುತ್ತವೆ.

ಆದರೆ ಎಲ್ಲಕ್ಕಿಂತ ತುಂಬಾ ಮೌನವಾದ, ಭಾವನಾತ್ಮಕವಾಗಿ ಆಳವಾದ ಕಲೆಯು ನಿಖಿಲ್ ಬ್ಯಾನರ್ಜಿ ಅವರ ಸಿತಾರ್. ಇಲ್ಲಿ ಯಾವ ತತ್ವವಿಲ್ಲ, ಯಾವ ಘೋಷಣೆಯಿಲ್ಲ. ಆದರೆ ಪ್ರತಿಯೊಂದು ನೋಟು ಕಾಲದ ಮಿತಿಯನ್ನು ಮೀರಿ ಹರಿಯುತ್ತದೆ. ಇದು ಯಾರು? ಏಕೆ? ಎಂಬುದಿಲ್ಲ. ಇಲ್ಲಿ ಕಲೆಯು ವ್ಯಕ್ತಿಕ ಮೌಲ್ಯ ಪ್ರತಿಪಾದನೆ ಅಲ್ಲ—ಇದು ತಾನೇ ಹರಿದು ಹೋಗುವುದು. ಆ ತಾಳ, ಆ ಲಯ, ಆ ನಾದದಲ್ಲಿ ಕಲೆ ವ್ಯಕ್ತಿಯ ಹುಟ್ಟುಹಾಕುವದು ಅಲ್ಲ, ವ್ಯಕ್ತಿಯ ಅಳಿವಾಗಿದೆ.

ಇವರೆಲ್ಲರೂ ತಮ್ಮದೇ ಆದ ರೀತಿಯಲ್ಲಿ ಕಲೆಯನ್ನು ಅತ್ಯಂತ ಗಂಭೀರವಾಗಿ ನೋಡುವವರು. ಆದರೆ ಕಲೆಯ ಬಗ್ಗೆ ಅವರ ಭಿನ್ನತೆಗಳು ಪ್ರಬಲ. ಅಯ್ನ್ ರ್ಯಾಂಡ್ ಗೆ ಶ್ರೇಷ್ಠತೆಯ ಆದರ್ಶವೇ ಶ್ರೇಷ್ಠ ಕಲೆಯ ಸ್ವರೂಪ. ಭೈರಪ್ಪರಿಗೆ ಸತ್ಯವು ಸಂಕೀರ್ಣವಾಗಿದೆ, ಸಂಶೋಧನೆಯ ರೂಪದಲ್ಲಿ ಬರಬೇಕು. ಡಿವಿಜಿಗೆ ಕಲೆಯು ಜೀವನದ ಋಜುತೆ, ತಾಳ್ಮೆ, ತೀಕ್ಷ್ಣ ನೋಟ. ಬ್ಯಾನರ್ಜಿ ಅವರಿಗೆ ಅದು ತಾನೇ ತೋಚಿಕೊಳ್ಳದ, ತಾನೇ ಬಿಟ್ಟುಕೊಡುವ ನಾದ.

ನಾನು ಈ ಎಲ್ಲಾ ಪುಸ್ತಕಗಳನ್ನು ಓದುತ್ತಿದ್ದೆ ಎಂದೆನಿಸಿದ್ದರೂ, ನಿಜಕ್ಕೆ ಅವುಗಳೆನ್ನನ್ನೇ ಓದುತ್ತಿದ್ದವು. ಈ ಕಲಾತ್ಮಕ ಚರ್ಚೆಗಳ ಮಧ್ಯೆ ನಾನು ತಿದ್ದಲ್ಪಟ್ಟೆ, ಅಳವಡಿಸಲ್ಪಟ್ಟೆ, ಮೌನವಾಗಲಾಯಿತು. ಕೆಲ ದಿನಗಳು ರ್ಯಾಂಡ್ನ ಸ್ಪಷ್ಟತೆಯಲ್ಲಿ ನಾನು ಮಿಂಚಿದೆ. ಮತ್ತೊಮ್ಮೆ, ಡಿವಿಜಿಯ ನಗುನಗಿಸುವ ತಾತ್ವಿಕತೆಯಲ್ಲಿ ವಿಶ್ರಾಂತಿ ಕಂಡೆ. ಭೈರಪ್ಪ ನನಗೆ ನೆನಪಿನ ಸಂಕೀರ್ಣತೆಯನ್ನು ಬೋಧಿಸಿದರು. ಬ್ಯಾನರ್ಜಿ ನನಗೆ ತಾನೇ ಇಲ್ಲದ ಹಾದಿಯ ಶ್ರದ್ಧೆಯ ಕಲೆಯನ್ನು ತೋರಿಸಿದರು.

ನಾನು ಕಲೆಯನ್ನು ಕೇಳಿದೆಯಲ್ಲ – ಕಲೆ ನನ್ನನ್ನು ಕೇಳಿತು. ಬಹುಶಃ ಕಲೆಯ ಅರ್ಥ ಅಷ್ಟೆ – ಕೇಳುತ್ತ, ಕೇಳಿಸಿಕೊಳ್ಳುತ್ತ ಸಾಗುವುದು.

------------------------------------------------------

Listening Across Worlds

Last month, I found myself drawn into a strange and beautiful confluence of voices. It started quite by accident — or maybe, as these things often are, by some quiet design I only noticed in hindsight. A dusty old copy of Atlas Shrugged found its way into my hands, its pages brittle with time but burning with an energy that I hadn’t encountered in years. Around the same time, I was revisiting Mankutimma’s Kagga, the kind of book that lives in the corner of your bookshelf like an old wise uncle, always nearby but rarely fully heard. And then there was Aavarana by S.L. Bhyrappa — a novel that doesn’t just tell a story but seems to tear through layers of inherited comfort. Through all of this, as day turned to dusk, I kept returning to the sitar of Nikhil Banerjee — flowing in the background like breath, like silence learning to speak.

What began as casual reading became something else entirely. These weren’t just books or recordings anymore; they were philosophical landscapes. They each had something to say — not about politics or society or even narrative — but about art itself. Why do we create? What do we express when we write, sing, carve, or compose? What does it mean to shape something, and in doing so, leave the imprint of one’s own metaphysics?

Ayn Rand was the first to state her case, with the sharp clarity of someone building not a book but a temple. For her, art is a recreation of reality, sculpted deliberately to reflect the artist’s deepest values. Not a mirror, but a vision. Art, to her, was architecture for the soul — you choose, shape, and present what ought to be. A novelist, then, is not just a storyteller but a moral engineer. A painter is a philosopher with color. A composer? Perhaps a mathematician of feeling. Her characters speak like thunderclaps — full of will, reason, and heroic ambition. There is no room for uncertainty, no tolerance for shrugging shoulders.

And yet, as I flipped between Rand’s fire and Mankutimma’s gentle rain, I began to feel the stretch of two very different worlds. D.V. Gundappa, writing in Kannada, in verses often just two lines long, offers something else entirely. His Kagga speaks not in declaration but in humility. Where Rand erects statues, DVG suggests we dissolve into the landscape. He tells us: become like oil on water — present, yet unattached. If Rand wants us to conquer the world with ideals, DVG wants us to live wisely within its contradictions. I imagined the two of them in conversation: Rand speaking of moral clarity, DVG replying with a half-smile and a story about a bird sitting on a moving bullock cart, thinking it was carrying the load.

And then came Bhyrappa, fierce in a quieter way. His Aavarana is not a sermon, it’s a wound being examined. Like Rand, he believes that truth matters. That memory matters. But unlike her gleaming certainty, Bhyrappa’s world is thick with history, civilization, burden. His characters carry not only their beliefs but the weight of ancestry and silence. He is not interested in the clean lines of abstraction. He digs into the uncomfortable — into caste, religion, politics — and refuses easy answers. If Rand’s art is about projecting values, Bhyrappa’s is about excavating them. I could see how both of them believe in moral reality. But where Rand speaks from the rooftop, Bhyrappa walks the ruins.

And yet nothing humbled me more than listening to Nikhil Banerjee. No words. No polemic. Just a raga, slowly unfolding like a river finding its way through the dark. Unlike the other three, Banerjee doesn’t construct a view of the world — he dissolves into it. His music is not about metaphysics in the Western sense. It doesn’t "represent" reality — it becomes it. Time bends. Thought recedes. What remains is a single note held long enough to reveal a universe inside it. If Rand’s art is the act of choosing what to portray, Banerjee’s is the act of surrendering choice altogether. To him, art is not expression, but immersion. Not statement, but offering.

It struck me that all four of them are deeply committed to art — not as ornament or entertainment — but as something sacred. Yet they disagree profoundly on what is sacred. For Rand, it’s the sovereign self. For Bhyrappa, the historical soul. For DVG, the ethical moment. For Banerjee, the silence between two notes.

And somewhere in the middle of all this — I sit, listening. Watching these ideas rub against each other like stones struck in the dark, hoping for a spark. Some days, I find myself nodding with Rand’s clarity. On others, I bow to DVG’s quiet smile. Bhyrappa reminds me that to understand the present, we must dare to confront the past. And Banerjee? He reminds me that sometimes the truest art is what flows when the ego finally gets out of the way.

I thought I was reading a few books. But really, I was being read. By ideas. By traditions. By silence. And in that strange conversation between worlds, I felt something deeper than agreement — I felt resonance. And maybe, that too is a kind of art.

Note:

I used ChatGPT to help structure and refine parts of this article — especially in translating scattered notes into a more readable narrative. The voice, decisions, and stories are mine; the AI was a helpful assistant in shaping them.

Comments